In September 2016, the John Scott−designed Visitor Centre at Āniwaniwa, near Lake Waikaremoana, was demolished by the Department of Conservation [DoC], despite vigorous protests from the architectural community and despite the building’s classification as a Category 1 Historic Place. The former Urewera National Park Headquarters was only 40 years old but had been empty for nearly a decade. DoC claimed that the building was an earthquake risk and that it had watertightness issues, but both claims were disputed by independent engineers and architects.

♦♦♦

Gone, like some beloved uncle, only worse. Not a natural death, but first a decade of neglect, then despatched unceremoniously by bureaucrats. John Scott is best known for his churches, particularly Futuna Chapel in Karori, Wellington, and Our Lady of Lourdes in Havelock North. But in the 1970s he designed a small gem for the National Park Board for use as its Urewera headquarters. He used a difficult site and built a reverential and intimate tribute to the bush and to the Urewera.

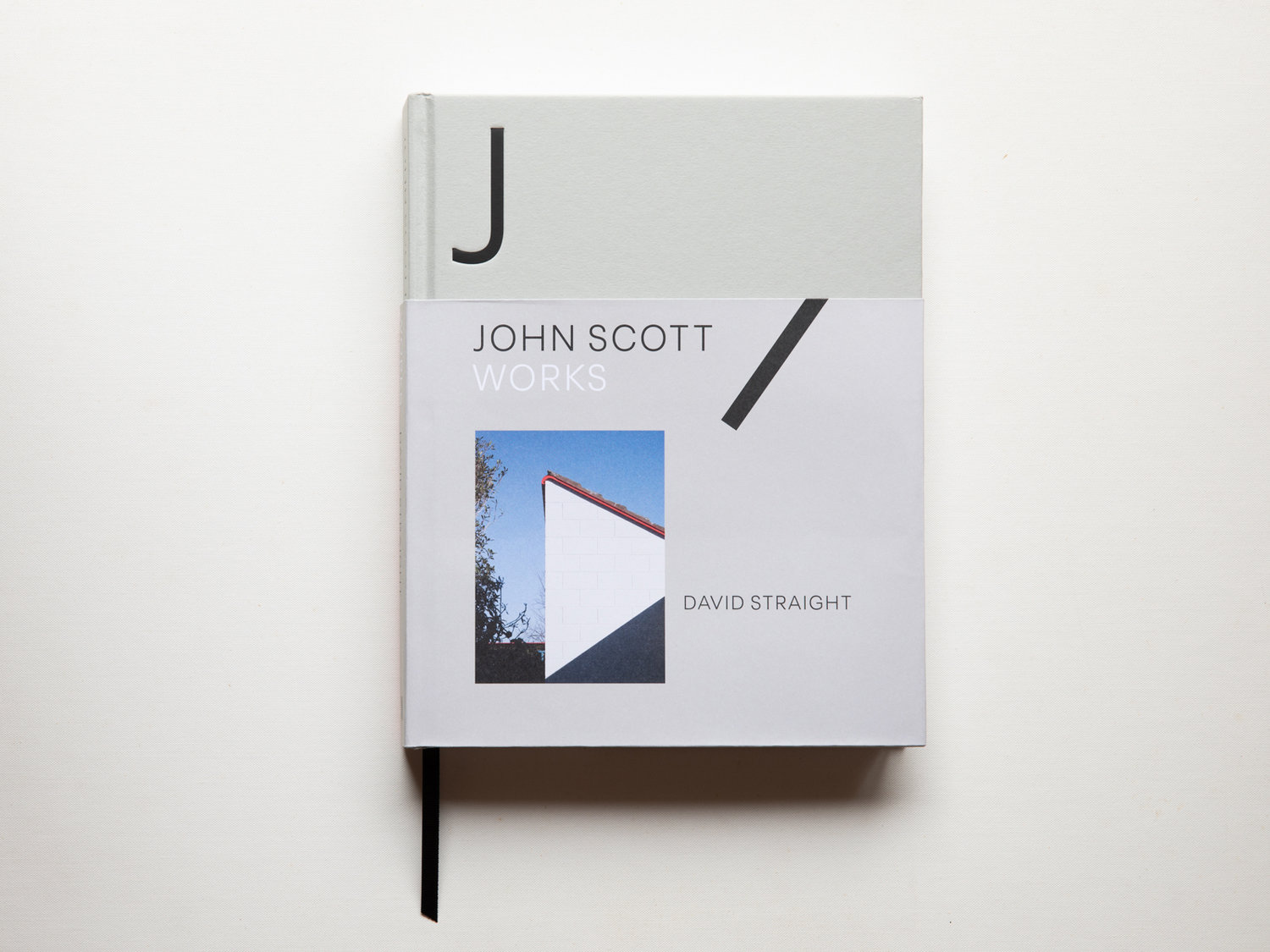

I grew up in a John Scott house and have had a lifelong interest in his architecture. I have photographed many of his buildings and made pilgrimages to his churches and public buildings, from Waitangi to Westport. Māori mythology is full of tricksters and mischief-makers. I think Scott is one of them. A shapeshifter. Scott’s work is cheeky, full of good humour and wit. He subverts conventions and pokes fun at the conventional. These are the qualities I like in his buildings.

In 2004 I drove the 750 kilometres from Nelson to Lake Waikaremoana to revisit the Āniwaniwa Visitor Centre. It was a long and winding trip. The bush in the Urewera is primordial. There is something ominous about this place, unwelcoming, its history uncomfortable for Pākehā. The Centre was several kilometres’ drive around Lake Waikaremoana towards the Āniwaniwa Falls, tucked in the bush off the road. To the side was a sheltered entranceway – a waharoa – that led to an elevated concrete walkway towards the back of the building.

The walkway was narrow in parts, then opening out onto larger balconies and up two series of steps to the door. Scott wanted you to enter through the bush, to be up in the trees, to hear the birds, feel the rain, breathe the air and smell the earth. Any other entrance would have been more practical but this way you understood the meaning of the building: it is both a tree hut and a church in the forest. At the top of the last set of stairs you were greeted by a round window and, to the left, wooden doors, painted orange. The windows had orange and yellow trim and wooden flaps for ventilation. The flaps and colours were common to many Scott buildings from the 1970s. Inside was an entry hall with vaulted wooden ceilings and black rafters. The spaces interconnected like a series of tents, each with windows of different shapes: square, rectangular, arched, and the round one in the entrance. All of them looked back out to the bush. The Visitor Centre was not a Māori building. It was a modernist building with Māori references. This is true of most of Scott’s work. His is an architecture to bring us together; it is about our similarities rather than our differences.

In traditional Māori architecture everything has meaning. The whare tipuna is the ancestor, the ridge pole is the spine, the rafters, ribs, and the maihi, arms. The building is the person and is rich in cultural symbolism both inside and out – the tukutuku a flounder, a stairway to heaven. Modernism abandoned the symbol. It is architecture where the wall is just a wall, where the structure is exposed and it means only to hold up the roof. It is concrete, not spiritual. Nothing is meant to be symbolic; the building is a machine. Modernism is architecture un-adorned – the building without baggage.

Scott’s buildings are intimate, and it’s an intimacy that is often lacking in modernist buildings. His work is warm in spirit, the volumes are human in size, the details subtle and simple. There are no grand gestures; the elements are integrated and complete the whole. Not only are the windows and walls well proportioned but also the size of the spaces, the heights, the light.

Scott’s subtlety and simplicity is not universally appreciated, particularly, perhaps, by politicians and bureaucrats. The lack of easy-to-read symbolism might be the flaw with the Visitor Centre. It was largely devoid of symbolic meanings, and those Scott included were new and hard to read. The windows were different shapes. Were they eyes or a mouth, a karu or a waha, or just windows? In a church the elements are easier to read; they all have names: the nave, the altar, the steeple, celestial light.

The process for developing the historic displays at the Centre was fraught and is still a sore point with Ngāi Tūhoe. The Park Board was staid and couldn’t find a place for genuine iwi input. Tūhoe offered to provide carvings for the building but this offer wasn’t taken up by the Board and the pou in the Māori gallery was left bare. I liked the naked pou.

The Park Board commissioned Colin McCahon to paint a mural for the Centre, to capture the spirit of the Urewera. There are ironies and contradictions in this choice and from the start the mural was controversial. Tūhoe wanted changes to the text and when it was installed staff thought it was overpowering. The Urewera triptych was stolen by Tūhoe activists as a protest in 1997 and returned almost a year later, adding to its fame. I’ve always found the mural a powerful piece of art. In the building it was like another window out to the spiritual past. It was also a statement about the here and now. Ko Maungapohatu te Maunga. Ko Tūhoe te iwi. Tau cross and five-pointed star, dark and brooding sky, stubborn bluffs: more modernism although this time with plenty of symbolism.

But the painting is problematic. The Visitor Centre was built to tell the story of the Urewera, but it was inappropriate for the Park Board to tell that story. In hindsight, it was probably wrong for McCahon to tell that story, too.

There is one word on the Urewera mural that encapsulates the essence of the issue. In the bottom right-hand corner McCahon has written “Their Land”. By “their” McCahon means Ngāi Tūhoe, and immediately places himself and the viewer as outsiders here. This painting needs to read “Our Land” but McCahon can’t paint that because although the Crown “owned” the land (had confiscated it) that wasn’t what he meant. The land was Tūhoe’s, the story was Tūhoe’s and the painting needed to be painted by Tūhoe and read “Our Land”.

This is fundamental to the cultural issues around the Visitor Centre and Tūhoe’s relationship with it. Tūhoe didn’t want those who had dispossessed them of their land to also take and tell Tūhoe’s story. Ngāi Tūhoe didn’t want the Visitor Centre as part of their Waitangi settlement. For them it was a symbol of colonial oppression and cultural misappropriation.

It surprises me how hard all this is, how far apart the world views are. It still surprises me how stubborn Pākehā are about learning te reo Māori, how our national day is still mispronounced.

Of course, there are tensions and history and baggage, but that is true of any meaningful journey. The cultural tensions added to this building, placed it at the heart of New Zealand’s developing biculturalism. If there wasn’t disagreement and conflict, there would be no progress. Scott’s building was part of that and part of our ongoing struggle to become bicultural. Heritage is important to us because it records difficulties overcome, journeys made, struggles resolved. Unfortunately, the history of the Visitor Centre at Āniwaniwa was not left to play out to its proper end but cut short somewhere in mid-life, demolished in the heat of the moment.

When I first visited in the 1980s I took two photos of the Centre: one of the McCahon mural inside; the other, the exterior from the road. In 2004 I was still using a film camera, with a 28mm lens or a 35mm tilt-shift and I took a roll-and-a-bit of film, perhaps 30 photos, which in today’s digital terms seems like way too few. Now that the building is gone and photos are all we have left, it seems a wasted opportunity. We have lost a building that is important to New Zealand architecture. Our architecture. Scott’s genius is that he created buildings that relate to this place, to us. He referenced our buildings: the barn, the woolshed, the wharenui, and he created, perhaps more than any other architect, a New Zealand vernacular.

It is gone because we lacked the goodwill and the cultural maturity to see the importance of the Āniwaniwa Visitor Centre and to appreciate its place in our architectural and cultural history.

Craig Martin

September 2016

From

here...

John Scott was an eminent New Zealand architect. He was born in 1924 and died in 1992, aged 68. My parents built a Scott house in 1970 and over the last 40 years I have visited and photographed many of his buildings. On this blog I'll post recent finds and new photos of old favourites, along with news and events that don't fit on my website www.johnscott.net.nz Click on the photos to enlarge.

John Scott was an eminent New Zealand architect. He was born in 1924 and died in 1992, aged 68. My parents built a Scott house in 1970 and over the last 40 years I have visited and photographed many of his buildings. On this blog I'll post recent finds and new photos of old favourites, along with news and events that don't fit on my website www.johnscott.net.nz Click on the photos to enlarge.